When people are mad at government, try legislative theater

/One of the flagship programs of People Powered is its Rising Stars mentorship program, which pairs experts with individuals who want coaching or some new ideas when planning or improving a participatory program. And now, a new, interactive tool is available to supplement the coaching process, guiding mentees through each step: the Participation Playbook. (In the fall, the playbook will open for public use.)

To explore the benefits of the mentorship program when combined with the playbook, People Powered Communications Director Pam Bailey interviewed Katy Rubin, a legislative theater mentor/playbook development consultant, and Nyasha “Frank” Mphalo, who leads the Green Governance Trust in Zimbabwe.

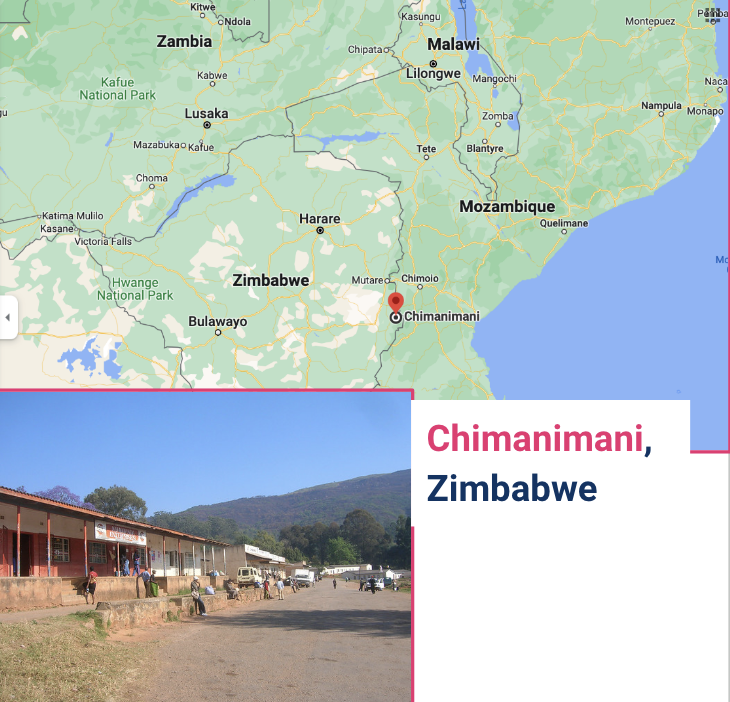

Last year, Frank participated in the first cohort of the People Powered Climate Democracy Accelerator. Now, with the help of a grant from the World Resources Institute, he is implementing the resulting action plan. Via a legislative theater project, young people ages 16-25, who are most impacted by natural disasters such as droughts and floods, are co-creating their district government’s climate change and watershed management plan.

Legislative theater is a type of participatory democracy designed to bring impacted community members together with government officials to better understand local problems and identify solutions, through drama.

Frank, what motivated you to seek mentorship through our Climate Democracy Accelerator?

Frank Mphalo

Frank: For the past four years, since Cyclone Idai impacted our communities, we have been working to promote citizen inclusion and participation in climate change decision-making. But we felt we weren’t really making much impact. The residents didn’t feel like they were being heard.

So, when I heard about the CDA, I knew it was a good opportunity to try some other method to get through to the local policymakers. Our district already had a climate change policy, but it had been lying unused in their offices for two years.

Why did you choose legislative theater as that “something new”?

Frank: I’ll be honest. I didn’t even know about legislative theater until I read about it on the People Powered website. Until then, I hadn’t thought that theater could be used to influence policymaking — especially not by engaging the decision-makers themselves in the actual production. It's something that’s never been done here before, at least in my community.

It took me a while to fully grasp it. Initially, I thought of it as presenting issues to people who are influential, showing how policy is actually implemented and how it could be done in a way that is better for affected communities. But what I hadn’t really internalized was that these influential people are actually part of the play. As a result, I would say the outcomes of the process are more impactful than I expected. Once they finally embraced it, they have been more willing to say things that they might not have said in a more formal meeting.

Katy: In different legislative theater processes, policymakers participate more or less, but at some point, they're always part of an interactive performance, and that means they're always taking some risks. But you can moderate how much risk-taking there is based on who your policymakers are and how much you want to build those relationships.

Katy Rubin

Katy, you’ve mentored many people in many countries on the use of legislative theater. What was unique for you in this assignment with Frank?

Katy: I felt super energized after our first meeting, because sometimes, when I mentor someone, they’re still worried about doing something different like legislative theater. You know, they fear no one will go for it or that it will be too risky. But Frank already “got” how theater can be useful, and the young people he had on board were excited about it. Plus, he was already collaborating with the local government council. So, he had all the pieces in place.

I didn’t have to explain to Frank that legislative theater is particularly useful when you’ve hit a wall with everything else. Frank was right where he needed to be to communicate to the other stakeholders why legislative theater was a really viable and necessary method at that moment.

I know from personal experience that government officials can be a hard sell when it comes to trying different engagement strategies. Frank, how did your council members react when you first proposed legislative theater?

Frank: It wasn’t easy at first. Legislative theater is not something most people are used to.

And I was quite anxious about what their response would be. I expected them to say, “We have never done plays. We want to be serious about things.” I wondered, too, if they would question if we were serious. But I banked on the relationship we had already built with the council over the previous four years. We weren’t coming from nowhere. We talk daily with them. Plus, our approach has always been less confrontational than other civil society organizations that speak against the council in newspapers, etc. Our idea is to say, “We're in this together. We just want you guys to make a commitment to addressing the climate issues we have.”

So, I said, “We’re in this together. Let’s try this model of engaging, on issues with the public.” They went along with me, but they weren’t really comfortable, or truly on board, until we actually started and they experienced what it was.

Katy, this is a common challenge, right? What advice do you offer?

Katy: It is a common problem. To be successful, you have to be stubborn and very committed, continuing no matter what. Fortunately, there's usually one person who is really into it, perhaps because they’ve done theater before, are more flexible, or simply are bored with their council job. So, you “lean” on them to pressure and encourage the other people.

What’s also unifying is the knowledge that engagement is important and the other things they’ve tried are not working, and now everybody is mad at them. Frankly, when everybody's mad at each other, that's a perfect time to do legislative theater. The shared goal is to make better policy that addresses people's needs and improves lives because it is informed by the people.

There's also another positive “side effect,” and that is relationship-building, a trust-building between citizens and their policymakers, who are also often local residents but we tend to see them as the “other.” And if we build trust, we also build goodwill that encourages people to come back and participate in other kinds of programs, like voting. Frank, you even told me in one of our last sessions that your team was finding that the young people involved are so excited that they are showing up for other things like research interviews. If you can keep those impacts front of mind for yourself and the policymakers, then you can encourage everyone to take some risks.

Frank: That’s true. These are straitjacketed people who are always wearing neckties. They weren’t comfortable with “playacting.” So, they made it clear they weren’t “going to get crazy.” Like Katy said, there’s one person who has emerged as a natural in this setting, perhaps because he did theater before. For the rest, it was scary. And I wondered if they would at some point say that they’re not going to continue with this because you’re just making fun of us. It was a matter of constantly reinforcing the commitment we all made to take this process seriously. But they are coming along now.

There’s another challenge we had at first that is unique to Africa: Involving youth in participatory democracy is rather disruptive, because it's sort of un-African for young people to question elders in public. So, we had to do it respectfully, within the context of Africanism. We had to teach the young people how to question elders in a way that is both respectful and that commands respect. It was very delicate. I would say that was the biggest challenge for us, but we managed to navigate through it by recognizing the values within our culture.

A young participant leads a ward-level legislative theater production.

How did you incorporate the Participation Playbook into the mentoring process, and in what way was it helpful?

Katy: We began each of our mentoring sessions by going through a section of the playbook. For example, the playbook begins by asking you to think through what your problem is and how you're going to get the desired participants on board. Fortunately, Frank already knew how to work the council, and that's half the battle. The other essential is having a trusting relationship with the community. Those are the two key requirements.

Then, as you go forward, the playbook guides you through the different phases, to help advance your project.

Frank: I found the playbook very interesting. When I first interacted with the playbook, I was curious to see how far it would take me. I found myself wanting to complete it all fast, to find out, “What's the next question? What's the next question? Where is it taking me?” When I reached the end, though, I went back, and that’s when you see the importance of a mentor. Because you start looking at what you've put down, what you’ve set out for yourself, and you start to question: “Is that really what I want to do? Will it give me results? Is it exactly what I want to pursue?” So, you start revising it, and then revising it again as it becomes more clear what you need to achieve. And at that stage, you might not be able to easily complete it by yourself without a mentor.

A mentor gives you someone with experience to ask, “What do you think about what I’ve proposed to do here? Is this something that will work?” You might have set very high standards that can’t be easily achieved. You don't want to find that out during implementation. I remember that in the beginning, my thinking was that we could do legislative theater with maybe 500 people in the audience watching. But now, the idea is to make the audience smaller, because we want to influence policy. We want it to lead to changes that are tangible. And that requires us to trim down the number of people who are part of it. These are the learnings you get from a mentor. By yourself, you might learn it too late.”

A significant contribution of the playbook is its logical series of steps it walks you through to achieve a certain result. Most of the programming we’ve done in the past has been a bit haphazard, because we were always pressing urgently for an immediate result, due to a non-action by our “duty bearers.” With the playbook, we were required to map out a logical series of actions, forcing us to be organized. we plan to use that approach with other projects, so there is a beginning and an end, with a specified series of logical activities in between.

The playbook is also good for helping you understand the “nitty gritty” part of the work. For us, it was important to understand in detail how it was all going to happen, who was going to be involved and in what way. How much resources would be required, etc. Without anticipating all of these details, we would find ourselves running out of resources, ideas or time because we didn't adequately think it through. The playbook is easy to share with the whole team, too, so you can discuss what you’re all committing to. I’d often say to Katy, “I'll go back to my team and get agreement, ask if this is feasible. Do we have time to do it in light of our other projects? Do we have enough resources?”

Katy: This kind of feedback from users like Frank is really useful. I am the author of the legislative theater section of the playbook, so I’m incorporating the feedback to make the playbook better. For example, Frank was initially confused about who the “actors” are in legislative theater: professional actors, or council members? That made me realize we need to make the description clearer. (The answer: The “actors” are not professionals! They are community members and government officials, acting out scenarios and solutions.)

It’s important for users to know that we use their feedback to further develop and improve the playbook. After all, once it's publicly available in the fall, not all users will have mentors to guide them, although we think that’s a good idea.

The value of having a mentor is that the playbook can seem a bit overwhelming when you go through it by yourself. “How do I answer all these questions?” It's less overwhelming, although it takes a lot longer, when you go through it with a mentor and think about it together. My suggestion is to think of the playbook as an outline of the things you need to think about. In fact, I’ve developed the playbook questions into a cheat sheet that I now use all the time as a sort of onboarding guide for city councils and other government agencies that are going to do legislative theater with me.

It requires them to think about who their community is, how these individuals can be identified and “resourced,” what the policy target is, whether anyone will be upset that they are taking on this issue, and how to build up to it. And then, once they’ve done legislative theater one time, and want to try it again later, they can go back to the playbook on their own as a sort of project-planning tool, unless they want some new ideas from a mentor.

Frank, what is the status of the productions at this point?

Frank: We have organized three sessions to develop the scenarios, at the ward level. We recorded them so we can track where we started from and how we progress. We’ll conclude with a larger legislative theater performance on August 10 at the council level.

In terms of who will attend, it will be controlled so we can achieve our goals -- the people who represent the community and the council staff themselves who represent the decision-makers. After that, we’ll follow up on the commitments. For example, we want a budget for disaster risk management and safe houses where people can go for protection.

Now that you’ve completed the mentorship process in the context of the Climate Democracy Accelerator, what advice would you offer others who are considering enrolling in the program, or signing up for a mentor independently?

Frank: 1) Be fully committed and have a clear idea of what you and your organization want to achieve. 2) Don’t expect it to be easy. 3) Expect to do some “unlearning.” If you're in the civil society space, we all have certain pre-existing ideas about how to do things. Remember that you’re trying something different to get better results. So, you need to unlearn some of the things you're used to, and be able to adapt to a new style of thinking and implementation. 4) You must be resourceful. I’ve learned that there's so many resources that are out there beyond my own organization. Take advantage of them!

Katy: Be able to answer the question, “Why this work, right now?” Know where you're going and what you have to work with. I’m glad to learn that in the next cohort of the accelerator programs, more resources are available so all the participants will get some implementation money. We aren’t operating in an imaginary world; all these activities cost money. If we're going to put the time in to plan it, we need money to make it happen. We don’t want to talk about participatory democracy in a theoretical sense, but in a practical way, and then have the resources to back it up. One other thing: Don’t just settle for policy proposals. You need to see them implemented, and keep following up. Sustain people's excitement and keep them engaged. After three to six months, you’ll see where the gaps still lie and what participatory process is needed next. It's a cycle.