Chilean institute harnesses digital platform to engage young people as change agents

/One of the Colchane residents who has received a sun-protecting hat, thanks to one of the youth projects (photo by Gonzalo Vera Santis)

Youth are the leaders of tomorrow (and today!), and progress toward a sustainable environment can only be made with their full engagement. Chile’s National Youth Institute understands this, and knew that to involve as many young people as possible, a digital platform was needed. It chose CitizenLab, and this post explains how the institute uses it to find and develop new leaders. This is part of a series of stories on digital participation platforms produced with the support of TICTeC. To read others in the series, see these case studies from China, Kyrgyzstan and Argentina.

Gonzalo Vera Santis, 29, grew up in Antofagasta, a port city in northern Chile. When he graduated from medical school at the age of 25, he couldn’t afford going on to study for his chosen specialization in dermatology. So, he enrolled in a government program that incentivizes medical students like him to practice in under-served regions before going on to specialize.

Gonzalo’s assignment is to work as a general practitioner at the clinic in rural Colchane, a tiny community on Chile’s border with Bolivia. The population of about 500 is mostly made up of the indigenous Aymara tribe and reports the country’s highest rate of people living below the poverty line.

“I live there Monday to Friday and spend the weekends in Iquique, the regional capital (about three hours away),” Gonzalo explains. “During the week, when I have off time, I’ve had to develop new hobbies, since it is so rural in Colchane. So, I taught myself photography, focusing on the diverse flora and fauna of the highlands.”

Gonzalo with some of his photos, in front of the Colchane welcome sign

As he observed the people, both in the medical clinic and in the community, he noticed their chronic exposure to intense sun; their insufficient or nonexistent use of hats, sunscreen lotions and other protective measures; and the resultant high incidence of skin and eye disease.

“There is extreme poverty in the Colchane commune and the people toil for long hours out in the sun,” explains Gonzalo. “They lack both the education and supplies needed for adequate sun protection. At the same time, I was recording these hardships with my photography.”

He’d long wanted to develop a social-change project of his own to help the people and, Gonzalo thought, maybe he could help by using art to raise awareness and his medical background to educate. But he had no idea how to organize or raise funds for such an initiative.

A Colchane man stands in the glaring sun in front of the heat-reflecting desert

Creamos: a government initiative to develop youth leaders

That’s when Gonzalo discovered Creamos (“We Create”), an initiative that popped up while he was scrolling through his Instagram feed one day. A program of the Chilean government’s INJUV (Instituto Nacional de la Juventud, or National Youth Institute), Creamos was launched in 2019 to prepare young people aged 15-29 to be “leaders for social change,” improving the quality of life in their communities and territories.

The impetus for the program was a finding that only 12% of young Chileans were leading or organizing local change and nearly half (47%) felt negatively about their opportunity to express their opinions and participate in civic life.

Creamos was introduced as an antidote of sorts: Young people are invited to pitch ideas for projects that align with one of the United Nations’ 17 sustainable development goals (SDGs). If their proposal is accepted (based in part on votes from fellow youth via a digital platform), they go on to receive training in leadership and project management, as well as personalized mentoring. Their fully developed project plans are then evaluated/voted on again, with the winners receiving an implementation grant.

Benjamin (standing, left) interacts with young adults participating in Creamos

“Our main objective is to empower young people and develop their capability to be productive, both for themselves and their community,” explains Benjamín Prado Larraín, manager of Creamos. “Our focus is on the person, but we also want to encourage them to participate in social issues and engage in community development. In Chile, [the government is] trying to connect with the real problems of the people. And we want to involve young people from the beginning, to be part of the solution.”

Benjamín believes that offering youth and young adults more opportunities to shape public policy and propose projects will help prevent the type of protests that broke out throughout Chile, primarily in 2019-2020, in response to trends such as a rising cost of living, privatization of public services and growing inequality. In fact, during the recent effort to draft and adopt a new constitution (recently put to a vote and rejected), Creamos held discussion sessions with youth in all 16 regions of the country, involving more than 3,000 young people. Their input was passed on to the drafters of the proposed constitution.

“In the beginning, youth development wasn't my thing,” he says. “But now I’ve seen the importance of young people’s development. They are creating the world of the future. The vision they have now is how the future of the world will go, including how we all participate in that.”

-

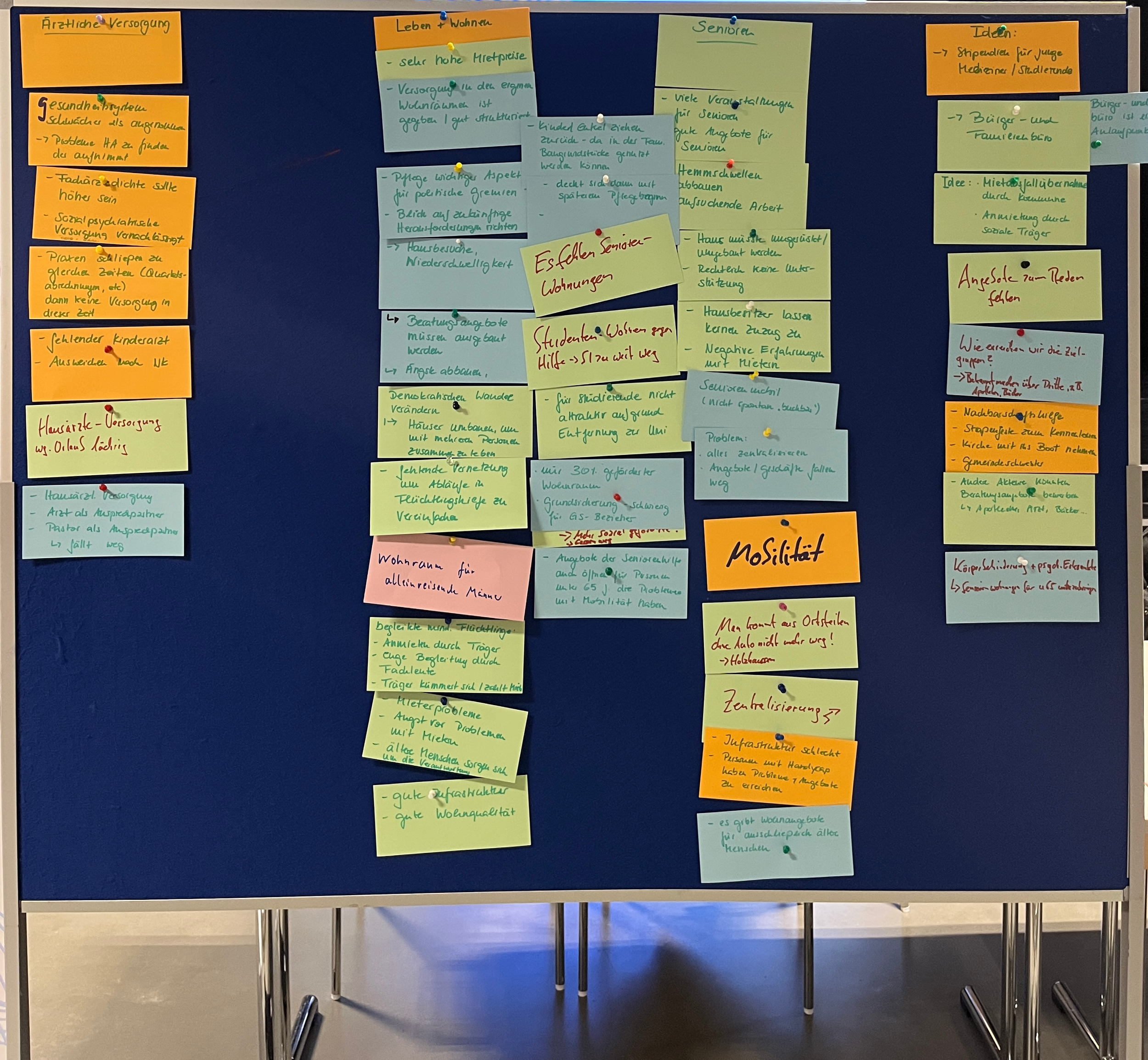

What challenge was Creamos created to address?

What is Creamos’ theory of change?

Could this approach work among youth in your area? How would you adapt it?

Assuring broad participation by going digital

Before Creamos was launched, says Benjamín, INJUV offered other programs to engage young people in civic participation, but none of them lasted due to design flaws. In addition, he notes, most of the previous activities were focused on political engagement. Creamos, which he helped establish three years ago, focuses specifically on youth leadership and participation in civic life writ large.

To attract broad engagement by Chile’s youth and young adults, INJUV chose to use CitizenLab, which bills itself as a “citizen engagement platform made for local governments.” It is one of the highest-ranked comprehensive participation platforms in the People Powered ratings. (People Powered also produced a guide to selection of digital platforms.)

“We chose CitizenLab because it has been used in so many other countries and has a lot of experience behind it,” explains Benjamín. “Idea collection is the main feature we needed. We want young people to participate, and the CitizenLab platform is easy-to-use and attractive. They can upload videos and share their proposal using social media buttons.”

Gonzalo considers it a good choice. “I found [the platform] very entertaining and user friendly. I was able to not only apply and vote, but also learn about other social projects, both in my region and in the rest of the country. I particularly liked the ability to upload my photos and videos.”

-

What features were important to Creamos when deciding which digital platform to use?

Which digital features did Gonzalos like the most?

What are/would be the most important criteria when choosing an online platform for your context?

The CitizenLab platform shows number of likes and comments for submitted ideas

There are six steps in the Creamos leadership-development process. Here’s how the online platform is seamlessly integrated:

Application. Ideas are submitted via the CitizenLab platform, with extra points given during evaluation if a video is included. In addition, prospective participants are linked to an application they must complete that includes a personal profile and explains their motivation.

The data produced by the platform show that ideas related to improving health and welfare are the most popular, followed by environmental initiatives.Voting. There are more than 45,000 people registered on the Creamos platform, and all are eligible to vote for up to five of their favorite ideas and make comments. In 2022, 985 comments were posted and 5,284 votes were logged. Each regional INJUV director is required to comment on each idea as well.

Regional evaluation. At the same time that applicants’ peers are voting, the INJUV regional directors evaluate the submissions for admissibility (based on program eligibility) and rate them according to the number of votes they receive (the most heavily weighted factor), clearly identified target audience, documented need, potential for success, scope of likely impact, etc.

Selection of applicants/ideas for further development. Each region is allowed to send an allocated number of applicants to the Creamos training and development program. In 2022, there were 594 ideas posted and a maximum of 450 could be selected. After the voting and evaluation process, 435 were sent on to the training and mentorship stage.

Leadership training, project development and mentorship. During this 12-week stage, done mostly via Zoom, participants also learn how to design, develop and manage projects.

Second round of voting/evaluation. When the ideas are fully developed into projects, they are posted on the CitizenLab program once again and subjected to a final round of voting and regional evaluation. “This is the toughest part for my team,” notes Benjamín, “because we can afford to fund implementation for only 30.”

Implementation.

The “back end” of the CitizenLab platform shows the number of registered and active users, along with a lot of other useful information.

-

What did Creamos do to help participating youth have the skills needed to develop viable proposals?

What was the overall challenge the national youth agency faced when choosing which projects to fund?

Are there any implementation steps you would add or eliminate for this type of project to be successful in your own context?

Gonzalo submitted his idea in 2021, was selected and participated in the training.

“The education and training I received in sustainable development and the design, implementation and evaluation of social projects were invaluable; it has really given me a confidence boost to keep developing my own initiatives in the future,” he says.

Benjamín observes, “Something I have learned over these years is that some young people have a real drive to be leaders. Creamos is especially fit for them. It’s like they were waiting for a program like this and we’re really just a tool for them. We want to find these young people, like Gonzalo, to connect the work to better programs for all people, especially vulnerable people in isolated places.”

Gonzalo went on to the implementation stage, and today, his project is complete.

The first phase raised awareness among residents of the damage caused by ultraviolet radiation. He did this in part by exhibiting his photographs of the commune’s iconic inhabitants, showing the effects of chronic sun exposure. The photos were accompanied by brochures with tips for prevention, including proper hats, glasses and sunscreen. And the clinic offered home visits to check for cancerous skin changes.

In the next stage of the project, wide-brimmed hats with neck protection were delivered, along with lip and skin cream. Finally, the photographs used for the exhibition were donated to the people portrayed.

“The Creamos program, including the connectedness I felt through the online platform, given my remote location, not only allowed me to develop and implement a project, but also gave me the tools, knowledge and education necessary to develop more initiatives in the future,” says Gonzalo. “There are a large number of young people with ideas but due to ignorance and the lack of a supportive community, they cannot carry them out. Hopefully, as Creamos continues, that will change.”

Key lessons

Benefits of digital participation platforms

Established platforms offer a community of users.

Allow video/photo uploads.

Attract youth and young adults.

Help residents learn about issues and ideas in other communities.

Platforms can be used for engagement in diverse institutions and organizations, not just government.

How to use digital platforms effectively

Provide training to help participants develop and improve their proposals. [Creamos uses a variety of platforms, including Moodle and Zoom.]

Form an expert review committee to evaluate the proposals.

Connect platforms to other digital channels, such as social media.

Integrate online platforms into overall programs, rather than treat them as stand-alone.

Ready to explore further?

Visit the People Powered Digital Participation Platform Guide and ratings.

Sign up for coaching by an experienced mentor.

Subscribe to the People Powered newsletter if you have not already, to learn about upcoming workshops, courses and other learning opportunities.